In 2026, International Migration, a peer-reviewed journal published by Wiley in collaboration with the International Organization for Migration, released a landmark study titled “The Social Psychology of Kafala: Structural Inequities, Intersectional Harms and Host Society Narratives in Lebanon.” Authored by Rhea Al Riachi and Jasmin Lilian Diab, the study offers one of the most comprehensive analyses to date of how Lebanon’s Kafala sponsorship system produces not only legal and economic exploitation, but also deep and enduring psychological harm to migrant domestic workers (MDWs).

Moving beyond conventional legal or labour-rights critiques, the study introduces a social-psychological and intersectional framework to understand how exploitation is normalised, reproduced, and internalised, both by institutions and by society at large. In doing so, it provides critical insights highly relevant to Lebanon’s human rights obligations, accountability mechanisms, and ongoing debates on labour reform.

Situating Kafala as a System of Structural Violence

The Kafala system in Lebanon ties a migrant domestic worker’s legal residency to a single employer, effectively granting employers control over mobility, employment continuity, and, in many cases, access to justice. While this system has long been criticised for facilitating abuse, Al Riachi and Diab demonstrate that its harm cannot be understood solely in contractual or legal terms.

The study argues that Kafala operates as a structural determinant of mental health, embedding dependency, surveillance, and racialised hierarchies into everyday life. Migrant domestic workers, primarily women from Ethiopia, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Kenya, and the Philippines, are positioned at the intersection of gender, race, class, and legal precarity. These intersecting identities expose them to heightened risks of psychological distress, including anxiety, depression, trauma, and feelings of disposability.

Crucially, the authors show that psychological harm is not incidental but systemic, arising from prolonged powerlessness, isolation, and the constant threat of deportation or retaliation.

Host Society Narratives and the Psychology of Exclusion

One of the study’s most original contributions lies in its analysis of Lebanese host-society narratives. Drawing on social psychology, the authors examine how moral hierarchies, ingroup/outgroup dynamics, and racialised labour norms normalise the marginalisation of migrant domestic workers.

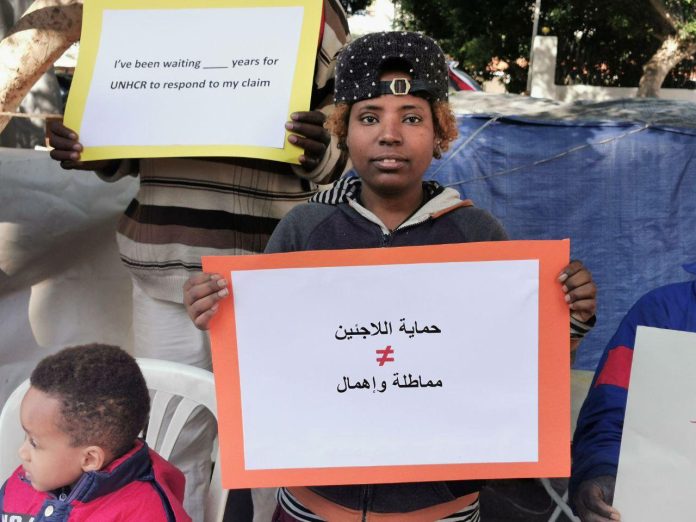

Migrant workers are frequently framed as temporary, subordinate, or outside the moral community deserving of protection. These narratives become especially visible during crises, when resources are scarce and social boundaries harden. The study documents how, during Lebanon’s overlapping crises, including the economic collapse, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the Beirut port explosion, migrant domestic workers were often excluded from aid, shelter, and psychosocial support.

This exclusion, the authors argue, is not merely administrative. It reflects processes of moral exclusion, whereby suffering is rendered invisible or socially acceptable because it occurs outside the perceived boundaries of national responsibility.

Crisis as an Amplifier of Psychological Harm

The August 4, 2020 Beirut port explosion serves as a critical case study within the research. Many migrant domestic workers lived in severely affected neighbourhoods such as Karantina, Bourj Hammoud, and Ashrafieh. The explosion resulted in sudden homelessness, job loss, and acute trauma.

Yet the study highlights that the blast did not create new vulnerabilities so much as intensify pre-existing ones. Workers already experiencing abuse or confinement found themselves abandoned by employers, excluded from emergency responses, and left without access to mental health services. Loud noises, instability, and ongoing insecurity triggered long-term psychological effects, including sleep disorders, panic, and chronic anxiety.

The authors frame this as a cyclical dynamic: structural exploitation generates mental distress, while mental distress further constrains workers’ ability to seek help or escape abusive conditions.

Methodology: A Trauma-Informed, Qualitative Approach

Methodologically, the study adopts a qualitative research design grounded in intersectionality and social psychology. Data collection combined a systematic desk review with in-depth semi-structured interviews conducted between September 2023 and September 2024.

Participants included migrant domestic workers with diverse nationalities, legal statuses, and employment arrangements, as well as stakeholders such as service providers, advocates, legal experts, and community organisers. Recruitment was conducted through purposive and snowball sampling, with support from migrant-led organisations, enabling access to highly marginalised and undocumented workers.

The research was explicitly trauma-informed, prioritising informed consent, participant safety, linguistic accessibility, and psychological well-being. Interviews were conducted in Arabic, English, Amharic, Bengali, and Sinhala, with professional interpretation where necessary. Data analysis relied on thematic coding, integrating inductive insights from participants with deductive frameworks drawn from intersectionality theory and social psychology.

Ethical approval was granted by the Lebanese American University Institutional Review Board, and all data were anonymised to protect participants from retaliation.

Coping, Resistance, and the Limits of Resilience

While documenting profound harm, the study also highlights migrant domestic workers’ agency and resilience. Workers mobilise a range of coping strategies, including solidarity networks, religious practices, digital organising, art therapy, and community-based initiatives. Migrant-led groups play a particularly vital role in providing shelter, psychosocial support, and legal guidance.

However, the authors caution against romanticising resilience. In the absence of systemic reform, coping strategies often function as survival mechanisms rather than pathways to well-being. Some workers resort to harmful strategies, including substance use or survival sex, underscoring the cost of prolonged structural neglect.

Implications for Human Rights and Accountability

The study concludes that meaningful reform requires more than minor adjustments to contracts or service provision. It calls for dismantling both the legal architecture of Kafala and the social-psychological mechanisms that sustain it. This includes integrating domestic workers into labour law, ensuring non-discriminatory access to mental health services, regulating recruitment agencies, and confronting societal narratives that legitimise exclusion.

For human rights institutions in Lebanon, including the National Human Rights Commission, the findings underscore the necessity of treating migrant domestic workers’ mental health as a human rights issue, inseparable from legal status, dignity, and equality before the law.

By linking lived experience to structural analysis, Al Riachi and Diab’s study offers a powerful evidence base for advocacy, policy reform, and international accountability efforts aimed at ending systemic exploitation and restoring human dignity.

هذه المقالة متاحة أيضًا بـ: العربية (Arabic) Français (French)